Once more, I offer my annual list of the seemingly-arbitrary “worth repeating” (given ‘best’ is such an inconclusive, imprecise designation), constructed from the list of Canadian poetry titles I’ve managed to review throughout the past year. This is my eleventh annual list [see also: 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011] since dusie-maven Susana Gardner originally suggested various dusie-esque poets write up their own versions of same, and I thank her both for the ongoing opportunity, and her original prompt.

I’ve reviewed and posted more than one hundred and forty poetry titles (most on the blog, but some over at periodicities) over the past calendar year (not including chapbooks, non-fiction and fiction titles, literary journals, etcetera) and am well over twelve hundred interviews into the “12 or 20 questions” interviews over the past fourteen years (which is ridiculous, honestly). Naturally, I’m frustrated about all the books I haven’t quite got to yet, and there are more on that list than I’d like to admit to. There were so many things! Probably twenty or so full-length works by Canadian writers I had hoped to get to this year, but haven’t quite managed yet. Might 2022 be any different? I did take a couple of days around Christmas to read comics, and I’ve been working more on my novel (again) over the past month (and working through edits of my suite of pandemic essays, composed during those first three months of original lock-down). I mean, I do other things, right? Right.

This year’s list includes new full-length poetry titles by Paul Pearson, Christopher Patton, Sarah Venart, Lindsay B-e, Phil Hall, Jessi MacEachern, Therese Estacion, Janet Gallant and Sharon Thesen, Bardia Sinaee, Conor Mc Donnell, Dennis Cooley, Aaron Tucker, Stephen Collis, Khashayar Mohammadi, Mary Germaine, Roxanna Bennett, Ken Norris, Sarah Burgoyne, Tara Borin, Barbara Nickel, Selina Boan, Anna Van Valkenburg, Hoa Nguyen, Kama La Mackerel, Lillian Nećakov, Andrea Actis, Bren Simmers, Jen Sookfong Lee, Margaret Christakos, Larissa Lai, Anahita Jamali Rad, Leah Horlick, George Bowering, Nora Collen Fulton, Angela Szczepaniak, Liz Howard, Leanne Dunic, Megan Gail Coles, Colin Smith, David O’Meara, Kevin Andrew Heslop, Helen Hajnoczky, MLA Chernoff, Síle Englert, Dale Martin Smith, ryan fitzpatrick, Isabella Wang, Rita Wong, Renée Sarojini Saklikar, David Bradford, Assiyah Jamilla Touré, Tom Prime, Ken Belford and Camille Martin. How does this list manage to get so much longer every single year?

I couldn’t get to everything, but I should also mention some stunning prose from the past year or so, including George Bowering’s Soft Zipper (Vancouver BC: New Star Books, 2021) [see my review of such here], Mark Goldstein’s Part Thief, Part Carpenter (Toronto ON: Beautiful Outlaw, 2021) [see my review of such here], Jordan Abel’s incredibly powerful NISHGA (Toronto ON: McClelland and Stewart, 2021) [see my review of such here] and Kirby’s Poetry is Queer (Windsor ON: Palimpsest Press, 2021) [see my review of such here]. If you don’t know by now, be aware that everyone needs a copy of Ottawa Amanda Earl’s groundbreaking anthology Judith: Women Making Visual Poetry (Malmö, Sweden: Timglaset Editions, 2021) [see my review of such here].

Obviously, this has been a further year of upsets, chaos and uncertainty. We lost more than a few this year, including Michael Dennis [see my obituary for him here; and poem for him also], Douglas Barbour [see my obituary for him here], Peter Van Toorn, Lee Maracle, Phyllis Webb [see my poem for her here] and Marie-Claire Blais. And Joan Didion! After seeing the documentary on her a while back, I actually began reading her work last year. And now, Betty White. Damn. But we are moving through, and will come out the other end; perhaps a little worse for wear, but there we’ll be. I’m counting on it.

Here is, yet again, my list of “worth repeating”:

1. Paul Pearson, Lunatic Engine: From Edmonton poet and Olive Reading Series co-founder Paul Pearson comes the full-length debut, Lunatic Engine (Winnipeg MB: Turnstone Press, 2020), a poetry collection with a hefty, multiple-part preface/introduction, outlining how, why and how much this book owes a debt to American writer Dava Sobel’s Galileo’s Daughter: A Historical Memoir of Science, Faith, and Love (Penguin Books, 1999), a book “based on the surviving letters of Galileo Galilei’s daughter, the nun Suor Maria Celeste, and explores the relationship between Galileo and his daughter,” and Letters to Father: Suor Maria Celeste to Galileo, 1623-1633 (Penguin Books, 2001), an assemblage of letters translated, introduced and annotated by Sobel. Through the poems of Lunatic Engine, Pearson interplays two distinct threads—of both celestial (including notions of God and of Galileo’s explorations of the universe) and domestic examination—and writes out, as part of his preface, a semi-facetious “INTRODUCTION: THEMES FOR BOOK CLUB,” that lay out the six concerns of the larger collection: “The relationship with your father, stargazer, absent parent,” “The death of your mother,” “The love poems, your relationship with your spouse,” “Becoming a father (and the deep concern that you’ll do it right),” “The mirror world of Galileo and his daughter—another complex but loving relationship” and “The drive to understand the universe, then and now, given the tools we have.” It is a curious way to not only shape a poetry collection, but to offer as outline those same structures. Rife with footnotes, his preface offers, these “are also fragments from the letters between Galileo and his daughter—as if they were commenting on phrases in this book,” and the interplay is intriguing. “To be so close to the truth,” he writes, as part of “SINCE THE LORD CHASTISES US / WITH THESE WHIPS,” offering the footnote: “it is certain that when we possess this treasure / we will fear neither danger nor death [.]” Pearson’s poems offer explorations on some pretty hefty concepts, and the interplay of the minutae of daily interaction in curious ways, writing on faith, marriage, parenting and loss, and the possibilities and impossibilities of all of the above. See my full review here.

2. Christopher Patton, Dumuzi: Canadian poet Christopher Patton’s latest title is Dumuzi (Kentville NS: Gaspereau Press, 2020), a a poetry collection that follows his poetry debut, Ox (Montreal QC: Vehicule Press, 2007), as well as his Medieval translations Curious Masonry (Gaspereau Press, 2011) and Unlikeness Is Us: Fourteen from the Exeter Book (Gaspereau Press, 2018). Having established himself as having an interest in exploring and reworking older source texts, Patton’s Dumuzi appears a blend of those two earlier threads of his publishing history, composing a translation inasmuch as Oh Brother, Where Art Thou? can be seen as a translation of The Odyssey; both rework from the bones of their original sources, and through the creation of a new and original work, uncover previously unseen meaning and depth from such ancient texts. Dumuzi tears apart and reworks old Sumerian myths into an assemblage of lyric fragments and sketches, as he explains as part of his essay “THE GOD DUMUZI AND THE POLICE FORCE INSIDE”: “I see now that my pleasure in pattern for its own sake, there on the signal-noise threshold, was an approach to translation. I was working with the Sumerian myths of Inanna and Dumuzi. Their stories are liturgically redundant, enough so to alter your time-sense, when you’re inside them. And a persistent theme of the poems is the agon, if you like, of form and formlessless.” Dumuz reworks an ancient tale through the building-blocks of language itself, opening with a short suite of establishing poems to set the foundation of his narrative before the narrative fractures and fractals out in multiple directions. It is as though Patton works translation, mistranslation and misheard translation, utilizing the loose structure of the ancient Sumerian stories and utilizing his play from those ancient bones. See my full review here.

3. Sarah Venart, I Am The Big Heart: Montreal poet Sarah Venart’s second full-length poetry collection is I Am The Big Heart (Kingston ON: Brick Books, 2020), an exploration of empathy and moments small and large, writing a lyric of time and of heart. A follow-up to her full-length debut, Woodshedding (Brick Books, 2007), as well as her chapbook Neither Apple Nor Pear, Weder Apfel Noch Birne (Toronto ON: Junction Books, 2003), the poems in I Am The Big Heart are organized into five sections of poems—“The Big Heart,” “Still Full of Arrows,” “Flowers for All Occasions,” “The Heiress” and “Joy in the Cloisters.” These are poems of dark heartbreak, pulling at the threads to examine how it emerged, is constructed, or even how it all falls apart. Part of what makes her notion of the “confessional mode” so compelling is the density and the slant of her narratives. Her lines wrap themselves around her subject with incredible precision, but never to obscure, even when she isn’t writing in a direct, straight line. Venart focuses on the minutiae, writing of domestic labour that predominantly falls on women; there is a coiled tension in her lyrics, which are quite different than the narrative stretches and comparatively-open sprawl of New York poet Rachel Zucker’s similar lyrics on mothering and domestic tensions. She writes on longing, desire and desperation; hard-won hope and the determinations of daily living. Venart writes on the largess of emotion, including how big an early crush on a neighbour boy feels in the chest. See my full review here.

4. Lindsay B-e, The Cyborg Anthology: Poems: I’m fascinated by the full-length debut by Toronto poet and filmmaker Lindsay B-e, The Cyborg Anthology: Poems (Kingston ON: Brick Books, 2020), an anthology shaped around speculative fiction, exploring ideas of consciousness, being, artificial intelligence and technology. The Cyborg Anthology: Poems examintes a potential future involving the rise and fall of cyborgs, and an acknowledgment of their literatures. Opening with the two authors of the “Early Cyborg Poems” section, the book is structured with a trio of Cyborg poets in each of the successive sections: “The Rise of the Cyborg Poets,” “Poetry and Politics,” “Celebrity Cyborgs – The Golden Age,” “Pop Culture Poets” and “Cyborg Poetics – The Next Generation.” And why wouldn’t future potential cyborgs be poets? “I live in this body,” Theseus (2125-2202) writes in “Everybody Else Has the Stomach Flu,” “but I don’t know it that well. // I don’t even know if this poem will end / with a rejection of my inheritance // or a mad dash down the hall / to spill my contents / into an open receptacle / with a well-defined inside / and outside.” B-e writes seventeen different speculative Cyborg poets, all of which are included with author biographies, including Patterson Armitage (2099-2191), who “composed a series of poems that were published in a short volume called Doodles. Each page contained a concrete poem that was drawn with his printing tool fingers.” Another is Mi’La Palpetit (2204-), “one of the few new Cyborg poets of this generation. She sports a set of ornately-carved wooden mechanical arms and legs. Born after the flare, Lalpetiti was raised next door to a small-town library in Nunavut and spent her childhood and youth absorbing the contents of the books. Her parents were members of the Ministry of Urban Rebuilding and would often take their children with them as they travelled.” See my full review here.

5. Phil Hall, Toward a Blacker Ardour: Perth, Ontario poet and editor Phil Hall’s latest full-length collection is Toward a Blacker Ardour (Toronto ON: Beautiful Outlaw, 2021), published by friend, collaborator and designer of a number of Hall’s Book*hug titles, poet and critic Mark Goldstein. Toward a Blacker Ardour is one of three full-length titles that Beautiful Outlaw has just released (alongside a translation and a collection of essays, both by Goldstein himself) which shifts Beautiful Outlaw’s long running enterprise of publishing very occasional chapbooks into something just a bit bigger. Over the years, Hall’s poetics and poetry collections have evolved from individual poems collected into books to individual book-length projects constructed out of poems to where his work currently lives: a kind of continuous, evolving through-line exploring a collaged sketch-work of ideas on writing, biography and personal history, trauma, reading and thinking, utilizing poem-fragments as building blocks that accumulate into further extensions of an ever-expanding poetic. He lingers, there. He lingers, as much as he might carve away through revision, a suggestion he has referenced multiple times, pulling his language back towards a “silence” he never manages to achieve (or can’t possibly avoid). Each thought, through his lyric, turned and turned over, so as to catch a different side of it, possibly; a different angle of light. Structurally, there is something of the accumulation of short stanzas of dense lines and couplets, alternating slight indentation, that Hall has latched onto as his best thinking form, and this, in many ways, allows for a sense of ongoingness between his published collections. One poem, one might say, to paraphrase Charles Olson’s “Projective Verse,” must immediately and directly lead to a further poem; each book, as well, leading directly to the next. See my full review here.

6. Jessi MacEachern, A Number of Stunning Attacks: Montreal poet Jessi MacEachern’s full-length debut is A Number of Stunning Attacks (Picton ON: Invisible Publishing, 2021). The lyrics of A Number of Stunning Attacks accumulate into a book-length suite around orientation and self-examination, lyric intimacy and presence, and the workings of the body and gender. “For our feminine organs,” she writes, as part of the third section, “there will be no meaningful study / the heart may think it knows better //// & grow quiet [.]” Composed as a sextet of serial poems—“The Moat Around Her Home,” “Stagger and Sing,” “Notes on Moving,” “A Miniature Gender,” “A Number of Stunning Attacks” and “Orwomen”—A Number of Stunning Attacks is constructed via short, accumulative bursts, quick lyric sketches that layer, stretch and weave. Hers is a lyric across an incredibly wide canvas. “Without her human limbs she was unable to carry / something other than herself,” she writes, as part of the third section, “Is real / the day is like his straying [.]” See my full review here.

7. Therese Estacion, Phantompains: As the copy on the back cover of Toronto poet Therese Estacion’s debut poetry title, Phantompains (Toronto ON: Book*hug, 2021), reads: “Therese Estacion survived a rare infection that nearly killed her, but not without losing both her legs below the knees, several fingers, and reproductive organs. Phantompains is a visceral, imaginative collection exploring disability, grief, and life by interweaving stark memories with dreamlike surrealism.” Phantompains exists very much as a kind of poetry memoir, utilizing the narrative lyric to record and examine trauma, pain and recovery while moving through the new and uncertain shapes and responses of and her own body. The sequence “Report on Phantompains,” which provides the book’s title (or vice versa), sits in the third section, and offers a description of phantom pain while navigating the physical and physiological trauma of what her body has lost. “There is a difference between phantompain / and phantomsensation,” she writes, as the eighth section of the extended prose lyric. Later on in the same piece: “my heart cramping up / like a charley horse [.]” Documenting her experience through the lyric, Estacion’s book-length poem aches to understand what it is she has lost, and how to wrestle her way to how best to move forward, fully aware that the shadow of these losses might never fully disappear. The upending trauma and loss Estacion articulates in the opening sequence, as well as throughout the book, is palpable, powerful and unmistakable. See my full review here.

8. Janet Gallant and Sharon Thesen, The Wig-Maker: I’m fascinated by the collaborative lyric memoir-in-poems by Janet Gallant and Sharon Thesen, The Wig-Maker (Vancouver BC: New Star Books, 2021), a harrowing account of childhood physical and sexual abuse, the suicide of a sibling, abandonment, grief and resilience. The poems in The Wig-Maker are told in the voice of the storyteller, Lake Country, British Columbia wig-maker Janet Gallant, as shaped by her neighbour, the poet Sharon Thesen, with the occasional aside by Thesen interspersed throughout. The poems in The Wig-Maker offer a memoir propelled by Thesen’s lyric clarity, writing out the story of Gallant’s life as a biracial child, abandoned early on by her mother, and left with her father and eventual stepmother. The narrative also includes Gallant’s more recent discovery, via DNA, that the man she knew as her father wasn’t her biological father, adding new layers and complications to an already fraught history. There are ways in which Thesen’s lyrics point to this process as an examination, documentation and potential exorcism of some of Gallant’s past, needing to say aloud in print what can possibly be set aside. The setting down of these poems might allow certain elements of Gallant’s past to be, finally, relegated to the past, with other elements recorded for posterity, and out of respect for some of those loved ones that she has lost, all of which build The Wig-Maker into a powerful, necessary and difficult collection. See my full review here.

9. Bardia Sinaee, Intruder: Award-winning Toronto-based former Ottawa poet (and In/Words editor) Bardia Sinaee’s long-awaited book-length debut is Intruder (Toronto ON: House of Anansi Press, 2021), a collection of smart, crafted, lyric narrative poems, rife with image and storytelling. “This / is my desert island mood,” he writes, as part of the poem “ALTHOUGH I AM ALWAYS TALKING,” “as free, surely, as I have / ever felt.” Later on in the same poem, offering that “Love / outside of habit / is occasional, punctuated // with fatigue, / like the weather.” The poems that make up Intruder offer an assemblage of short scenes or stories composed via the narrative lyric, thick with verve and detail. “You’re in a quiet place between / school and unemployment,” he writes, to open the poem “HIGH PARK,” “lying / down in the park with a scarf / over your face. I’ve brought a big, / boring book to press flowers in, though / these dandelions are awfully / juicy, don’t you think?” See my full review here.

10. Conor Mc Donnell, Recovery Community: Toronto poet and physician Conor Mc Donnell’s full-length debut is the poetry collection Recovery Community (Toronto ON: Mansfield Press, 2020), a book comprised through a poetry of direct statement. His appears as a poetics of subject, determination and sentences composed on and around health and the betrayals and limitations of the body. “I began a careless quark,” he writes, as part of the poem “Forget Galway,” “the question mark of everything I might become [.]” Structured through three untitled sections of poems plus opening poem, Mc Donnell’s Recovery Community writes around and through crises of health and the possibility of healing, writing the intimacies of crises and care through the ability, and even requirement, to depend upon others. “You were dying in a room where I usually work,” he writes, as part of “I’ll be there when you die,” “and I checked on you / every few minutes // I get caught with a patient and when I saw you again a colleague / was suctioning phlegm through the catheter he just placed / in your throat // The sound wakes you suddenly, panicked and wide eyed, / and you don’t know where you are [.]” Mc Donnell writes from both sides of the medical equation, from patient to physician, which can only provide deeper layers of comprehension and expertise. “I am in the eye,” he writes, to close the poem “The Lady Waits,” “but I cannot see to photograph. My life acquires an uneasy calm /// as when a baby comes and you are told not to push /// an ecstasy held up by pressure and pain /// I am in the eye of an emergency & I haven’t saved a thing /// There are cupids carved in the ceilings [.]” See my full review here.

11-13. Dennis Cooley, The Bestiary, cold-press moon and The Muse Sings: I know it isn’t impossible for a poet to publish three books in the same calendar year, but there aren’t many who see three poetry titles appear in the same season, let alone two with the same publisher. Winnipeg poet, editor, critic and teacher Dennis Cooley’s work has long been expansive, exhaustive and far-reaching, stretching across years and manuscript pages, and the second half of 2020 saw the publication of his collection of poems around prairie beasts, his collection of pieces reworking myths, fables and well-familiar stories, and his collection of poems around the idea of the muse. Cooley is a poet in constant motion, yet one that also doesn’t seem to publish much in journals, especially given how much he has produced. The Bestiary is exactly what one might suspect it is, a collection of poems on prairie beasts. Set into themed sections—“‘A Prairie Boy’s Eden’,” “THE FROGS,” “THE CROW,” “THE SPIDER,” “ARKOLOGY” and “THE BIRDS”—Cooley composes a lyric in constant motion, play and wit and bad jokes, a lyric that refuses stillness; even while describing stillness, merely a pause before the poem turns, and darts away. “an old hen /barred / rock they called Hetty,” he writes, to open the poem “Hetty,” “Ms. Hen Rietta Lamour / and she was slow and lame // also dingy among / the persnickety birds / the hennaed chickens / that mince & fluff / in near disdain pick over the jewels [.]” Exploring his list of prairie beasts and childhood attentions and recollections, his lines bounce across pun and play, allowing the motion of language to propel where it might next land, bouncing off an idea or a fragment or a word stepping forth. The poems in The Bestiary are securely placed, set in prairie locale and language, among the sounds and stretched-out silences of the long prairie grasses and ahems, the patters of Cooley’s speech. “ttsskk tskk a grim taskmaster,” he writes, as part of the poem “is a victorian schoolmater,” “brisks to the ledge / one swift pass / sideswipes winter / / swipes the board clean [.]”

cold-press moon works through well-familiar European stories and fables to classic monsters, writing stepmothers, Hansel and Gretel, The Brothers Grimm, Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. As the end of “The Forest” writes: “he hollows out a space in his heart for the words his chil- / dren carry in their pockets to warm all the stories they / ever heard or told [.]” Cooley has a way of arriving at the bare bones of a story, of an idea, writing landscape or folk tales of lost children and stepmothers, and what moves out beyond the shadows. He even includes a sly reference to his friend David Arnason, who wrote out two volumes, subtitled “fractured prairie tales,” of own short stories reworking fables and myths, both of which appeared through Turnstone Press: The Dragon And The Dry Goods Princess (1994) and If Pigs Could Fly (1995). As part of the piece “THE FATHER CONFERS WITH THE QUEEN,” a poem composed as part of a stretch of lyrics around the fable of the princess and the frog, Cooley writes out the queen, who speaks: “No, I simply will not hear this. That wonderful / Mr. Arnason know who knows all about these things from his / days at Gimli says he’s quite remarkable at the pool, a fine / young swimmer. A natural. And that is the end of it. I / will not hear another word.” There is something so compelling in the way his poems push, propelled by sound, ideas and image, endlessly pushing alternates and versions, such as the poem “GARRISON MENTALITY,” the first poem of the section “Rapunzel,” that begins: “awful the way you keep me // waiting why lady chat / elaine why do you do this / you into your curds & why // i send my feathered love / the shafts of light shift & sing / they ring & splinter against / your bedroom door [.]” Cooley writes so much around the core of a story, weaving an endless array of other threads and thoughts, composing poems as fragments, facets of the whole, set entirely in tandem with the rest of the collection, potentially incomplete outside of the larger manuscript.

The poems of The Muse Sings examine the act of writing and how poems emerge, moreso an act of creation from within and surrounded by the tangible offerings of a community than the invisible hand of any of the nine Greek Muses. As he writes as part of “Dear Dubé,” a poem “for Paulette Dubé” thar references “Our Lady / of Perpetual Help Pool Hall,” “i want to be part of the thousand / shocks flesh is err to / that pool of help & forgiveness // exactly when, their lines true, they clear the table / with all the joy & clatter they can muster [.]” He writes of his muse, his musings; of friends and influence, astonishments, hopes and disappointments, even as he dedicates the collection to Mnemosyne: the Greek goddess of memory, and, according to Hesiod, the mother of the nine Muses. Cooley muses, and offers this to that which has prompted, influenced, and even amused, fueling his own ongoing works. And then, of course, another reference to David Arnason, in the poem “world of reference,” which is dedicated to him. As the poem ends, Cooley writing out the place where the two might still be able to meet, in the space of the written and printed page: “the long path our words follow / through swinging gates / we are paging one another [.]” See my full review here.

14. Aaron Tucker, Catalogue D’oiseaux: I’d been curious to see the full-length poem that makes up the continued, ongoing present of the lyric of Toronto poet Aaron Tucker’s third full-length poetry title, Catalogue D’oiseaux (Toronto ON: Book*hug, 2021). Catalogue D’oiseaux is a single book-length poem composed in birdsong, writing, as the back cover offers: “a year in the life of a couple separated by distance, carefully documenting time spent together and apart. When reunited, they embark on travels across the globe—from Toronto to Berlin, Porto to the Yukon.” “I in Toronto amid the chills off Lake Ontario,” he writes, early on in the poem, “comforted only by those long flights to you / when I looked out the window at the clouds & the bent horizon / the sun rising above it & the ocean below [.]” The intimacy and the narrative expositions are a shift from the structural concerns of his first two, far more constraint-based, poetry titles: Irresponsible Mediums: The Chess Games of Marcel Duchamp (Bookthug Press, 2017) and punchlines (Toronto ON: Mansfield Press, 2015). In an interview posted January 1, 2018 over at the ottawa poetry newsletter, conducted by Ian Whistle, Tucker references composing poems that could very much be the opening strains of this collected lyric. As he offers: “I’m writing weird little bird-lyric poems based on some of the travelling I have been doing. I’m not exactly sure what they are, or what they might become, but I’ve enjoyed writing them so far.” Tucker writes on reading, travel, musical composition, writing and long distances, allowing the flourishing of this new relationship, this new connection, to hold as the central basis of the poem’s strength and momentum. There is something interesting in the blend of the intimately personal and the structural that Tucker explores in this singular poem. It is comparable, in a certain way, to the human elements that Canadian poet Christian Bök allowed in the text of his most recent volume, The Xenotext Book 1 (Coach House Books, 2015). The intimacy allows the structure of Tucker’s Catalogue D’oiseaux it’s heart, propelling the mechanics that allow the machine to live. See my full review here.

15. A History of the Theories of Rain, by Stephen Collis: Vancouver poet, writer, critic, literary activist and 2019 Latner Writers' Trust Poetry Prize winner Stephen Collis’ latest is the poetry title A History of the Theories of Rain (Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2021), a lyric quartet that writes specifically on and around the implications and ideas of the ongoing and increasing global climate crisis. “Give me music because // I never could understand its // direct connection to // that feeling stream,” he writes, as part of the untitled opening lyric. Collis’ work has long explored the possibilities of what poetry might accomplish, responding to ongoing social concerns through poetry titles such as Anarchive (Vancouver BC: New Star Books, 2005), The Commons (Talonbooks, 2008/2014), To the Barricades (Talonbooks, 2013) and Once in Blockadia (Talonbooks, 2016). Over the years, his poetry has explored social concerns and engagements, writing and living his politics around decolonization, authority, land rights, the oppositions to the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion and the ongoing ecological crisis. His work is immediate, timely and timeless, providing amplification to what the lyric has long held as a quiet, underlying thread; by Collis, this eco-poetic is not mere flowering, but magnified. It is through such work, and the ways in which he has crafted his complex lyric of attending the unfolding these crises that Collis has become one of our most essentially-engaged contemporary poets. His, alongside the work of contemporaries such as Rita Wong and Christine Leclerc, is a rare lyric that includes actual action, as, during his participations in the protests against the Trans Mountain pipeline, he was sued by Kinder Morgan for five-point-six million dollars. “and we were not afraid,” he writes, as part of the second section, “and held each other / with our very voices // molten / in the ubiquitous dark / not brittle really / not beaten back / but material still / and here to bend the light [.]” Collis argues for acknowledgment, as well as the required response, which at the very minimum, requires the notion of resistance. See my full review here.

16. Khashayar Mohammadi, Me, You, Then Snow: An Iranian-born writer and translator based in Toronto, Khashayar Mohammadi is the author of the long-awaited full-length poetry debut, Me, You, Then Snow (Guelph ON: Gordon Hill Press, 2021), a book of lyric compassion, epistolary gestures, film references and porn stars, and first-person explorations of memory, dreams, desire and personal histories. “You’re aching,” he writes, as part of the poem-section “Dear Kestrel,” “and while aching / you promise yourself you’ll be beautiful forever [.]” Later on, in the poem “Bergman’s ‘Persona,’” he writes: “to see oneself in the actress / is to make a leap of faith / a cultural martyrdom / of imagery [.]” The poems in Me, You, Then Snow accumulate into a collection of response poems, placing the narrator in the world in relation to those around them. In poems such as “Canada Day 2019,” “Greg’s goodbye party” and “Pastoral,” Mohammadi centres the narrative “I” in relation to other people and experiences with travel, love, desire and media, all of which reaches out as a way to explore inward. Poems that seek connection, safety and love. The title moves, ripples, outward from “Me” to “You” and then the abstract-beyond, “Then Snow,” all of which seems to sum up perfectly the perspective here, although with a looking outward in part to better comprehend the self, and the narrator’s relationship with any and all else. “I hone my desire to feel more in tune with my past,” he writes, as part of “No pockets ghazal,” “unibrow beauty hairy arms beauty [.]” Or the poem “Anemone,” that opens: “When I speak of the body, I speak / of its ability / to reconnect and repair [.]” See my full review here.

17. Mary Germaine, Congratulations, Rhododendrons: I’m fascinated by Fredericton-based poet Mary Germaine’s lyric scenes, displayed through her full-length debut, Congratulations, Rhododendrons (Toronto ON: House of Anansi Press, 2021). Congratulations, Rhododendrons is a collection of poems braided together from odd musings, recollections and observations, and long stretches of lyric that run out and across beyond the patterns of narrative sentence. Consider the title of the poem “The Look on Your Face When You Learn / They Make Antacids Out of Marble,” and its subsequent opening: “Who knows the name of the empire that took your arms, or the earthquake / that left you to drag your way, legless, to the top of the rubble.” Her perspective is delightfully odd and slightly skewed. Uniquely singular and refreshing, Germaine provides new life into the narrative-driven lyric. Consider, too, the title of the poem “Upon Hearing How Long It Takes a Plastic Bag to Break Down,” that includes: “”We built them to make it easy / to carry groceries, gym shoes, / shorelines, treetops, and dog shit. / And they do. And they will, until the end / of time, or the next five hundred years— / whichever comes first. I will be buried / and I’m not sorry some plastic will outstay / my appreciation of sunsets. I suspect even sunsets / will be garbage by then.” The scenes she writes out and the points within that she highlights are fascinating. “If you don’t love me then there’s no / seeing each other around,” she writes, as part of the poem “Valediction,” “not dressed like this. Look, / our separate fatigues / blend us with the scenery: / a scrim of any busy station, / a busy life in the blue distance.” Her narratives are playfully, subtlely odd, writing a resigned, sly wisdom and melancholy that emerges only through experience, and the maturity of a writer usually further along than that of a full-length debut. There aren’t too many poets that manage to emerge seemingly out of nowhere, so confident and fully-formed. Just where has she been hiding, this whole time? See my full review here.

18. Roxanna Bennett, The Untranslatable I: Roxanna Bennett’s third full-length poetry title, after The Uncertainty Principle (Toronto ON: Tightrope Books, 2014) and unmeaningable (Guelph ON: Gordon Hill Press, 2019), is The Untranslatable I (Gordon Hill Press, 2021), a further exploration of what has been dubbed “disability poetics,” writing both the visible and the invisible. Across forty-three first-person lyric narrative poems, Bennett writes a suite of prefixed titles, repeating prefixes such as “Travel Diary,” “Purplefish Key,” “CBT Worksheet,” “Postcard from the Bottle City of Kandor,” “Gratitude Journal” and “Babelfish Key,” referencing the fictional fish one puts in their ears to simultaneously translate spoken language as it moves through the ear, from Douglas Adams’ infamous The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Bennett writes around and across explorations of the untranslatable self, exploring what Virginia poet Susannah Nevison describes as well, in a quote included at the opening of the collection: “Explaining disability is like speaking two languages, and it is it the disabled person who is required to translate for the able-bodied world.” In the poem “Babelfish Key: Stairs & Whispers,” as Bennett writes: “Can we make peace / of the many pieces a cracked keepsake makes // or keep making the same mistakes uncaring / whose being we break, identity not their commodity / but a story rewritten continuously, no body embodies // meaning more than another one?” See my full review here.

19. Ken Norris, South China Sea: Canadian poet Ken Norris is the author of a few dozen poetry titles (including two different volumes of selected poems) since the publication of his debut, Vegetables (Montreal QC: Vehicule Press, 1975). His latest poetry title is South China Sea (Toronto ON: Guernica Editions, 2021), a collection that, many ways, circles back to the travel-framing of his Islands (Toronto ON: Coach House Press, 1981). Whereas Islands focused more on the beginnings of his jaunts to foreign locales, the title of South China Sea instead offers poems on the journey itself, one that moves out into the world and back again across the length and breadth of his life. “And so the poet’s work / is never done.” he writes, to open the poem “INSTRUCTION.” In the same poem, further on, adding: “It’s all present, / often in the same moment.” The poems of South China Sea are composed with a directness that even offer him as a tourist in his very skin; small moments, gestures and reminiscences lived and recalled at a slight distance. Norris isn’t a poet composing self-contained carved-diamond lyrics of exposition or wisdom, but one seeking the wisdom across a broader spectrum. To understand the nuance of his poems, one must read across a wider swath of his work, and a collection such as this is very much constructed as a singular project. “Nothing heroic in any of it,” he writes, to open the poem “LIFE,” “and yet it was life. / It was all that we had.” The wisdom of Norris’ lyrics emerge through the less obvious, the slow gradient of his lyric, using poetry as a way through which to articulate the moments of his own experience and connections. And, being a memoir-in-verse, certain poems in South China Sea harken back to certain other, smaller projects and collections. See my full review here.

20. Sarah Burgoyne, Because the Sun: Montreal poet Sarah Burgoyne’s latest poetry title is Because the Sun (Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2021), a book composed as a quartet of lyric and prose sections: “one, the sun,” “two, the sky,” “three, women” and “four, flowers.” The author of a handful of chapbooks both solo and collaborative, this is Burgoyne’s second trade poetry title, after the award-winning Saint Twin (Toronto ON: Mansfield Press, 2016). As she describes through the notes at the end of Because the Sun, Burgoyne writes the facets of the sun from Camus, and the point at which Camus’ novel and the film Thelma and Louise (1991) meet. “here is the closed room,” she writes, as part of the poem “WHAT WAS / ENFANCE,” in the first section, a poem that cities itself as “after Rimbaud,” “behind the chrysanthemums, the / dead little room and its mat of astroturf, the whole sky is / luminous (in the room), and the great obstacle is what has / already taken place.” An earlier version of that section, also, was first revealed as her “statement” to introduce her work as part of her participation in the “Spotlight series,” posted March 21, 2017. Burgoyne has previously done some stunning work with the prose poem form, especially the extended or serial prose poem, so it is fascinating to see her explore more conceptual frameworks through this latest collection. “a work of art is / a confession,” she writes, as part of the final section. The conceptual framework of Because the Sun works from Camus and Thelma and Louise, examining an array of sentences on and around the sun, but also explores the very nature of art-making, and the relationships language and art have with each other, artwork has with other artworks, and relationships those works might have with the audience/reader, including the narrator/creator of this particular work. One can create and even hide behind artwork, but it does not erase the creator; it does not provide a place from which to be completely invisible. “the tops / of buildings get a / little colder with all / the damning / evidence in our / hands we’re afraid / of punishment / we’re glad this / went nowhere” (“JACKPOT,” “four, flowers”). See my full review here.

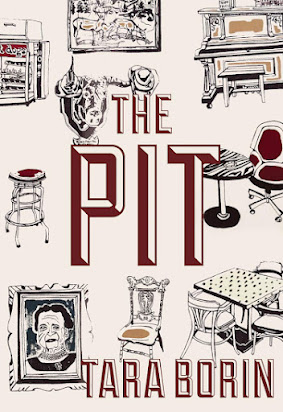

21. Tara Borin, The Pit: Dawson City, Yukon-based poet Tara Borin’s full-length poetry debut is The Pit (Gibsons BC: Nightwood Editions, 2021), a collection exploring the stories and setting of a local bar in “small-town, subarctic” space. Borin writes of “The Pit,” the oldest bar in the Yukon, run and patronized by locals and part of Dawson City’s Westminster Hotel. In The Pit, Borin writes the characters and experiences within what a hotel and associated tavern would hold in such a remote community, a combination of meeting point and last resort rolled into one; a point for community and communal events. “Here is where we find / the shortest distance / to each other:,” Borin writes, as part of the poem “DESIRE PATHS,” “bar top, schnaps sticky, / plywood dance floor / that feels like it could give / at any moment, / the house band a jukebox / onstage.” The Pit is composed as a quintet of portrait-sections, composing portraits of an array of characters in and around the space of the pub and hotel, whether short term or lifers, and everyone in between. As Borin writes as part of the poem “PORTRAIT OF THE RETIRED BARMAID”: “Snaps off the radio, her team // about to lose, / blows kisses to her cockatiel, / crest bobbing in his cage, // to the photos of her grandbabies / crowding the walls. // She slips into her old bomber jacket / with the bar’s faded pink logo / on the back.” Borin relays tales that could exist in any era, exploring a timelessness to such spaces, whether the 1960s, 1990s or more contemporary, writing tales of love and lost opportunities, sleazy attempts and comraderies, bar fights and addiction. As Borin’s narrator to the poem “HEARTBREAK HOTEL” asks: “How many heartbreaks / has this room held?” The collection might be well-populated, but examines predominantly solitary paths and solitary acts, dark stretches of addiction, loss and dead-end narratives, although all composed with a clear love for the space and its history, and of the characters collected within. See my full review here.

22. Barbara Nickel, Essential Tremor: poems: It is good to see a third full-length poetry collection by Yarrow, British Columbia writer Barbara Nickel, her Essential Tremor: poems (Caitlin Press, 2021), following The Gladys Elegies (Saskatoon SK: Coteau Books, 1997) and Domain: poems (Toronto ON: House of Anansi Press, 2007), as well as her collection of poems for younger readers, From the Top of a Grain Elevator (Vancouver BC: Beach Holme Publishers, 1999). The poems in Essential Tremor examine how to keep from getting lost, geographic missives and reportage, notes on her surroundings, offering “past / the tick-tock runway, docks, all moorings / recognizable or not, on the way to lost.” (“Passport”). “You ask me what I’ve given up: outside.” she writes, to open the poem “Anchoress (1),” “Need I elaborate?” She writes of the body, histories of loss and trauma, music and great stories, and poems that utilize Biblical passages as jumping-off points. She writes of the body, and the effect the world might have on it. “If only it were that: a little / trembling in the hand.” she writes, to open the title poem. “If we could tell / your leg be still and still it would.” The collection includes a selection of mirror-poems, but what really strikes in the collection, possibly as an anchor across the collection as a whole, is “Corona,” a sequence of thirteen pandemic-era lyrics individually dated from March through to September, 2020. The poems within “Corona” provide an immediacy, and even an urgency, to the collection, even if certain poems around and outside the sequence might have been composed years prior. Through the body and around it, the pandemic rages, writing both the intimacy of a body that requires protection, and an increased attention to the larger world, even through increased isolation. To open “10 (Essential),” she writes: “She walks ahead. We don’t touch yet / except this place within—my phone, her scroll / and fingerboard not skin but living, set / under her chin for life. She plays although / her audience has scattered into screens.” See my full review here.

23. Selina Boan, Undoing Hours: Vancouver-based poet and editor Selina Boan’s full-length debut is Undoing Hours (Gibsons BC: Nightwood Editions, 2021), a collection of lyrics on the intimate, the small and the immediate, writing on the “ways we undo, inherit, reclaim and (re)learn. Having grown up disconnected from her father’s family and community, Boan turns to language as one way to challenge the impact of assimilation politics and colonization on her own being and on the landscape she inhabits.” Writing in a blend of prose poems and traditional lyrics, often within the same poems, Boan’s phrases and sentences are exploratory, working to cover the ground of what she knows and remembers, attempting to work her way into what she wishes to discover and connect into, and just how much she might not realize she has already absorbed. As she writes to open the poem “my mother’s oracle card said”: “the answer is simple. take your mess, / bless it and start over.” There is a rawness to these poems; a vulnerability, writing carefully and openly, as best as possible, to reap whatever benefit might be possible. “i’ll admit,” she writes, as part of the poem “email drafts to nohtâwiy,” “i’ve been afraid to write. so here is my deflection, for / everyone to read.” See my full review here.

24. Anna Van Valkenburg, Queen and Carcass: Anna Van Valkenburg’s full-length poetry debut is Queen and Carcass (Vancouver BC: Anvil Press, 2021), published as part of Stuart Ross’ imprint, A Feed Dog Book. Born in Konin, Poland and currently residing in Mississauga, Ontario, Van Valkenburg works an assemblage of surreal tales and retold myths, twisting together the real and fabled, from Slavic folklore to her own engagements and observations. “I’m the bone in the soup,” she writes, to close the poem “LITTLE RED IN LOVE,” “the dog’s dark feet / after rain; what remains / when the second letter of the alphabet / bites the first while waiting its turn, / and the mother throws a scowl / like How could you ever think / you could talk to a wolf / and get away with it?” She works through unexpected corners of her own childhood library of references, from Grimm’s fairytales and Snow White to Baba Yaga. “A town is a tin of children / in an ocean.” she tells us, as part of “THE IMAGINARY TOWN OF GRIMM.” Further on in the same piece, she writes: “An ocean is an island. That’s a choice.” One could suggest the entire collection is built of poems composed from external jumping-off points, from artwork to writing to folklore, as Van Valkenburg breathes new perspectives out of and beyond already-familiar moments. “What’s in a carnival,” she asks, to end the poem “BRUEGEL’S LENT SPEAKS TO CARNIVAL,” responding to the 1559 painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, “The Fight Between Carnival and Lent,” “if not a prelude / to death? You forgot where it came from, / but they haven’t, and when they remind you // about the Creator, you will find / your hands in the dustpan, you will / teach them what it means to / force life to crawl out from its steel mother.” She works a curious blend of wistful storytelling and brutal truths, surreal takes with terrifying action, akin to fables themselves, writing dark tales of origins and forgotten lore, hidden just below the surface. Old ideas are hard to kill, after all, and sit below the skin of much of our forgotten truths, long-held beliefs and unacknowledged fears. “A library / in a language / no one can read.” she writes, to close the short poem “CULTURE.” Van Valkenburg writes of what is possible and what is impossible, and what should be equally approached with wonder, and fear. See my full review here.

25. Hoa Nguyen, A Thousand Times You Lose Your Treasure: To introduce a February 2018 profile on Griffin Prize-shortlisted poet Hoa Nguyen for the Saigoneer, Paul Christiansen wrote: “Before giving birth to her, Nguyen’s mother, Diep, motivated by a rebellious spirit and a difficult family life, fled her small village and joined the circus at age 15. After putting in time doing menial tasks for the outfit, she became a stunt motorbike rider in a famous all-female troupe—barreling perpendicular to the ground at breakneck speeds inside large domes without so much as a helmet or pads. On one occasion she even performed for President Ngo Dinh Diem. She crashed in front of him, but ignoring her tattered uniform and bloodied body, she steadied herself and got back on her bike to finish the performance.” (“A Vietnamese-American Poet’s First Return to Vietnam After Half a Century”). A Thousand Times You Lose Your Treasure (Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books, 2021) is an intimate and compassionate portrait of the author’s mother as a young motorcycle artist. There is a lightness to these poems, a delicate touch, but one that also threatens to drift away, given some of her mother’s uncertain recollections, allowing the past a tenuous tangibility. As with any family story, even at the best of times, there can be incomplete answers and half-formed questions, not always aware of how or even what to ask, and to whom. Throughout, Nguyen performes her own high-wire act, stepping point to point, even while writing across the shadow of the Vietnam War, motorcycle adventuring, stories of her biological father appearing in her mother’s life, and references to “the first Hoa,” much of which is set across the landscape of the Mekong Delta: “what electric ribbon of water / re- / becomes delta / fish and moving mouths / as the nine dragons move more” (“MUD MATRIX”). And of course, Nguyen writing the girl who would become her mother: “A motorcycle act that came to her province,” she writes, as part of “THE FLYING MOTORIST ARTIST,” “in the lower Mekong Delta / joining a country fair / for the New Year 1954 // everywhere we came to see / displays of snakes / contortionists / fortune-tellers / to exchange caged birds // she the disobey // Diệp done with farm chores [.]” These poems exist as an incredibly powerful elegy to connections lost and a life well-lived, and as both tribute to and portrait of her mother, capturing an array of moments that might otherwise have entirely slipped away. See my full review here.

26. Kama La Mackerel, ZOM-FAM: From Montreal-based multi-disciplinary artist, education, community-arts facilitator, performer and literary translator Kama La Mackerel comes their long-awaited debut, ZOM-FAM (Montreal QC: Metonymy Press, 2020), a book of unfolding questions, innovations and performances. Comprised of eight extended poem-performances that explore the past and the possibility of positive ways forward, ZOM-FAM is a flourish of lyric monologues examining family, family history; it is a book of gender and social structures and expectations, writing out a history of birth, rebirth, affirmation and resistance. “in 1986,” they write, as part of the extended “twenty years of brick,” “my parents absolve themselves from plantation heritage / signing themselves into a lifetime of repayment / their consent redeeming ancestral bonds // they buy a piece of land on which leans / a room / an outdoors toilet / an outdoors kitchen / formerly the residence of bann domestik / servants, on the edge of white people property [.]” The poems here are expansively performative and very physical, stretching out the possibilities of narrative flourish through the lyric, writing on race and gender, and notions of identity around colonization and the body. There is such an energy to this collection, and a performance that comes clearly through and across the page. See my full review here.

27. Lillian Nećakov, il virus: Produced as part of Cobourg, Ontario poet, editor and publisher Stuart Ross’ “A Feed Dog Book” imprint at Vancouver’s Anvil Press is Toronto poet Lillian Nećakov’s il virus (2021). As the press release offers: “il virus brings together 113 poems written over seventy-eight days during the spring 2020 pandemic lockdown in Toronto. These responses to daily news and eclectic media posts encompass dogs (lots of them), Zambonis, jazz and blues, Jackie Gleason, mathematics, thermodynamics, and geography (real and imagined). These miniatures are Lillian Nećakov’s most spare poems, but each is jam-packed with explosives: anger, grief, love, need, and a foraging for ink.” I’m curious at the suggestion of these as “miniatures,” as the interconnectedness of this suite of one hundred and thirteen numbered poems suggest them less as miniatures than individual points across a far wider expanse; the ongoingness of what, across seventy-eight days, developed from individual pieces posted to social media into a book-length response to those uncertain and unsettling early days of pandemic and lockdown. il virus does offer a kind of poetic diary of occasion and ongoingness, composed as an accumulation of meditations that move through the narrative points of those early weeks of lockdown. Known predominantly for her short, carved, surreal narrative lyrics, Nećakov instead employs a stretch of anxious meditation, contemplating the length of time almost exclusively spent at home amid family, attempts at distraction and the constant news cycle, as well as the echoes of the past, including the 1917 Influenza pandemic, and familial nodes of memory. She works her way through daily activities, some of which have been shifted due to the isolation, from listening to music or reading, to grocery store options and homeschooling. A low nervousness might have occasionally poked through the layers of her previous works, but il virus offers anxiety as an underlying, and entirely reasonable, response. As the seventh poem in her cycle opens: “After ten days of news, shouting, unbearable silence / we dust off the Grunow model 520 / turn the dial in search of / Radio Luxembourg / yes / we are old enough to remember / yes / we are old enough to die [.]” See my full review of such here.

28. Andrea Actis, Grey All Over: Poet and editor Andrea Actis’ full-length poetry debut is Grey All Over (Kingston ON: Brick Books, 2021), a book titled after the email handle of her late father, assembling the accumulation and detritus of loss and what remains. Structured in nine sections, Actis examines the limitations and the excesses of the archive, including photographs, emails, handwritten letters, old receipts and other scraps as the structure, the scaffolding, upon which her texts stand. Dedicated “For my dead dad,” Grey All Over explores how and through what process one grieves the loss of such a complicated person and a complicated relationship. There is a heft to this collection, moving through the intersections between two whole lives—hers and her father’s—including conversations with the dead and the remains of the dead. This is less a book of ghosts than, quite literally, memory and the archive, how one impacts upon the other, and how both allow, in their own ways, for interpretation and uncertainty. Messy, open and devasting, Grey All Over is composed as a poetry-memoir build as a scrapbook, both in form and in content: not seeking completion but an assemblage, where craft is less about the carved form than the consideration of memories, mementoes and, quite simply, what remains, whether from him directly, or through her. This is a polyvocal book exploring echoes on addiction, trauma, memory and conversation, all around a beloved parent that she found, at times, extremely difficult to interact with. Grey All Over explores the ways in which death prompts consideration and reconsideration, and, as Sachiko Murakami writes as part of her back cover blurb: “When a loved one dies, there’s all this stuff to deal with, and in the midst of grief we begin to collection, sort, document, store, and discard.” See my full review here.

29. Bren Simmers, If, When: Given how much I enjoyed her prior collection, I’d been curious about Canadian poet (currently located on Prince Edward Island) Bren Simmers’ latest, If, When (Wolfville NS: Gaspereau Press, 2021). Her third full-length poetry collection, If, When writes on a particular landscape of British Columbia, citing fishing and mining towns, moving through history and family histories, and connecting back to her great-grandparents who had emigrated to the same area from Scotland, a century prior to her own arrival. In certain ways, elements of Simmers’ west coast explorations of industrial work exist as both continuation and counterpoint to similar types of work-writing over the years by Barry McKinnon (pulp/log), Michael Turner (Company Town) or the late Peter Culley [see my obituary for him here]. “Some men stuff cotton,” she writes, to open the poem “WIDOWMAKER,” a poem subtitled “Dinty, 1914,” “in their ears to mute My great-grandfather / ghosting the margins. / the artillery of drilling rock.” She writes of work and industry, but only as an element of a larger structure of family relation and time, writing her immediate and the echoes of a century distant, and the lives of her great-grandparents through lyric description and short narrative bursts. Simmers’ work-to-date, through the poetry collections Night Gears (Toronto ON: Wolsak and Wynn, 2010) and Hastings-Sunrise (Gibsons BC: Nightwood Editions, 2015) and non-fiction Pivot Point (Gaspereau Press, 2019), are very much grounded in geographic and human spaces, writing the land and landscape upon which she exists, and If, When allows for a further consideration, that of the echoes of her own lineage across those same paths. “All his letters ink black by censors.” she writes, as part of the poem “AT LAST,” subtitled “Isabella, 1918,” speculating her great-grandmother’s thoughts at the end of the Great War. “Limbs intact / but his easy laugh? Time enough to reconcile the / men who left with the men who come home. / The men are coming home.” See my full review here.

30. Jen Sookfong Lee, The Shadow List: The author of five books of fiction and non-fiction, as well as four books for children, Vancouver writer Jen Sookfong Lee’s full-length poetry debut is The Shadow List (Hamilton ON: Buckrider Books/Wolsak and Wynn, 2021). There are far fewer examples of writers effectively moving from novels into poetry I can point to than examples of those working in the other direction (although Robert Kroetsch would be an example). I don’t even want to think about the times I’ve seen poetry titles by fiction writers that appear as little more than examples of prose broken into arbitrary line-breaks, but Lee clearly understands the form she’s working in, perhaps far better than many who claim such as their preferred form of composition. The Shadow List is an assemblage of raw, first-person lyric narratives that explore the complications of human interaction, pop culture and anxiety, from parents, parenting, texting and dating to teenaged diary entries, Harry Styles, sleepless nights and traumas, past and present. She writes very much in a confessional mode, one that interplays dark thoughts with humour and pop culture. Lee’s poems explore how life is lived, and even negotiated, on a very immediate level. She writes of hopes and shadows, muscle memory, intimacy and frustration, and possibilities that might not always be possible. “The hurt will fuck you up,” she writes, to end the opening sequence, “but you will appear fine and this, / above all else, is your gift.” What is interesting is in the realization that Lee’s poems don’t necessarily exist to fully exorcise dark content, but, sometimes, as repeated loops; the goal of writing out such dark thoughts isn’t to remove them from play but to set them into the light. This is one step in a sequence, not an end. Either way, debut or not, this is a compelling collection, one that explores realms so often presented as unseemly or unfitting of contemplation, let alone as the property of exploration through poetry. See my full review here.

31. Margaret Christakos, Dear Birch,: Toronto poet Margaret Christakos’ latest poetry title is Dear Birch, (Windsor ON: Palimpsest Press, 2021), a book that exists as a curious extension of the expansiveness of her poetry collections over the past few years. Her first few poetry collections, beginning with Not Egypt (Toronto ON: Coach House Press, 1987), were composed as self-contained poetry titles that wrapped poems in and around each other within the bounds of the individual collection, slowly evolving to work and rework her own texts in a way that reshaped both the language and thinking of her ongoing work. Her more recent collections, predominantly over the past decade or so, have explored larger structures and themes that seem to move through and across multiple book-length titles. Even the notion of the cycle, a self-described structure this collection shares with her prior collection, charger (Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2020), could be suggested as both an excised thread (from some larger, more ongoing consideration), and a journey that returns to where she began. The ten-poem cycle of Dear Birch, (yes, the comma is part of the book’s title) excises some of its poems from other of her publications, pulling from the chapbook Retreat Diary (Book*hug, 2005), her full-collections charger, Multitudes (Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2013) and Welling (Sudbury, ON: Your Scrivener Press, 2010), as well as through the non-fiction lyric of her remarkable lyric essay/memoir Her Paraphernalia: On Motherlines, Sex/Blood/Loss & Selfies (Toronto ON: BookThug, 2016). Through pulling from the threads of other collections, she simultaneously establishes something self-contained and reinforces the idea of how her published books speak and relate to each other. She writes of social media, intimacy and human connection and the shadow of her mother’s death; she writes of her adult children, who sit in close proximity, and her experiences and thoughts on dating sites and lovers, from those who have begun to drift away, to those potentially emerging across the horizon. She writes of the two poles of her life meeting, from the loss of her own mother to what her children will have to endure. See my full review here.

32. Larissa Lai, Iron Goddess of Mercy: A Poem: Better known to the wider public as the author of award-winning works of fiction, Calgary writer, editor and critic Larissa Lai’s latest is Iron Goddess of Mercy: A Poem (Vancouver BC: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2021), her eighth book overall and third full-length poetry title, after Sybil Unrest (co-authored with Rita Wong; originally published by Line Books, 2009; new edition with New Star Books, 2013) and Automaton Biographies (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2009). Iron Goddess of Mercy: A Poem is a book-length poem composed in sixty-four numbered sections, each with a single block of lyric prose accompanied by a clipped tercet, as Lai offers her own book-length take on the English-language adaptation of the Japanese utaniki. Known as a form of the poetic diary that combines elements of prose and poetry structures, the utaniki has been seen in Canadian literature through multiple poets exploring their own formal takes, including bpNichol, Fred Wah, Roy Kiyooka, Chris Johnson and even myself, for a time. There’s something of the call-and-response to the paired form, or even the Greek chorus (as well as linkages to work by Margaret Christakos and Joan Retallack, which I discussed recently, here), allowing the main body of speech and the follow-up of a combination of commentary and boiling down. And Lai has much in this collection worth discussing. Lai writes on global capitalism and environmental issues, colonization and occupation, pro-democracy protests across Hong Kong, and the umbrella terminology of “Asian” that too often reduces complexity down to a fixed and single, and, often misunderstood and misappropriated, point. She explores Asian-ness as well as anti-Asian sentiment and violence, and histories as relevant now as they’ve ever been. “Here’s a residue,” she writes, to end the prose-block of part fifty-six, “triple occupation as station of my grim asian hum dimming / the lights to find the truth of all that transpired after our / brothers un-ned us, I was so unhappy then, I’m happy now, / why would I want to remember? The secrets of Chinatown are / no secrets at all, ancient or otherwise, when subject’s a split / slit bleeding in the dark.” See my full review here.

33. Anahita Jamali Rad, still: I’m fascinated by the expansions of the first-person lyric as displayed through Montreal poet and editor Anahita Jamali Rad’s second full-length poetry title, still (Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2021), following their debut, For Love And Autonomy (Talonbooks, 2016). still explores an abstract and a light touch, sketching out reports on perception, writing, absence and inquiry, as the poem “LOG V” begins: “I waited so this day could pass / as if time itself // could determine / action // days that passed before / pass again, unfolding // dimensions of imagining // and still I / position my position // peripheral to the object [.]” still is a sequence of simultaneous calm and howevers, of wavering presence and time, and of logic, all of which operates on a deliberately-shifting foundation. The irony of still, of course, is that their poems are perpetually in-motion. “when there’s nothing left / in this,” Rad writes, as part of the poem “NEW CODES OF EXPOSURE,” “our abandon // our inward- / looking silence // clears nothing / and is simply // a hesitant wandering / a tiredness of talking or / unwillingness to speak // this word-filled space seeks / its own absence [.]” See my full review here.

34. Leah Horlick, Moldovan Hotel: To understand the impulse that propels Calgary-based poet Leah Horlick’s third full-length poetry title, Moldovan Hotel (Kingston ON: Brick Books, 2021), one needs to look no further than the notes at the back of the collection: “It’s a Jewish tradition to dedicate a period of study to a departed ancestor or teacher.” According to the back cover, Moldovan Hotel emerged when the author “travelled to Romania to revisit the region her Jewish ancestors fled. What she unearthed there is an elaborate web connecting conscious worlds to subconscious ones, fascism to neofascisms, Europe to the America to the Middle East, typhus to HIV/Aids, genocide in Romania to land grabs in Palestine, women’s lives in farming villages to queer lives in the city, language to its trap doors, and love to its hidden, ancestral obligations.” Horlick writes of grandmothers and Romanian villages, of escape and survival, and of some of the dark folds of European history, some of which continues, through the dark stain of contemporary fascism. “Europe inhales sharp and folds in / on itself. Its shoulder is a triple cross // stamped with iron,” she writes, to open “Europe Eats Itself,” “one elbow / is a flag // held the wrong way / on purpose.” She writes of the past, but very much aware of how the past impacts the present, often impossibly so. Through sharp, first-person lyric poems, Horlick works to explore those shifts and quiet erasures, and those spaces deliberately broken or hidden. She works to uncover stories, seeking to better understand her own relationship to trauma. As she writes, to open the poem “You Are My Hiding Place”: “The hole in the floor is old, old, old, country. / It lives under the kitchen table, yawns wide // While the family eats, wider still when they starve. / Cold above, so below. When the horses march up to the house, // the hole – it has teeth – it chatters. Grandma says the hole / is where the women go when the Russians come.” See my full review here.

35. George Bowering, Could Be: The latest collection of new poems by Vancouver writer George Bowering is Could Be (Vancouver BC: New Star Books, 2021), a collection of short lyrics that follow a lineage of other collections of short lyrics he’s published over the past few years, including his dos-à -dos flip book Some End/West Broadway (with George Stanley; Vancouver BC: New Star Books, 2018), The World, I Guess (New Star, 2015) and Teeth: Poems 2006-2011 (Toronto ON: Mansfield Press, 2013). While the projects themselves haven’t diminished, whether in number, size or scope, over the past twenty years—recent other titles of his include the non-fiction titles Soft Zipper (New Star, 2021) and Writing and Reading (New Star, 2019), the novel No One (Toronto ON: ECW Press, 2018) and short story collection Ten Women (Vancouver BC: Anvil Press, 2015)—his poems seem to have evolved from the multitudinous book-length project to these more recent collections akin to bundles of poems that interact in less obvious ways. This is the natural hope and progression for any writer still on their game, one might say, but not everyone manages to still produce engaged and engaging work so far into the process. Has George Bowering produced more than one hundred full-length books by now? Most likely, I would think, and anyone with even a fraction of that kind of back catalogue would be lucky to be still working at this level of complex ease. See my full review here.

36. Nora Collen Fulton, Thee Display: A third title by Nora Collen Fulton, following Life Experience Coolant (Toronto ON: Book*hug, 2013) and Presence Detection System (Philadelphia PA: Hiding Press, 2019), is Thee Display (2020), produced as “a joint publication of The Centre for Expanded Poetics and Anteism, Montreal.” As the project self-describes at the opening of the volume: “DOCUMENTS is the publishing imprint of the Centre for Expanded Poetics at Concordia University, Montreal. Our aim is to publish work attesting to the multiplicity of practices, techniques, and modes of theoretical intelligence that informs contemporary poetics. If poetics refers to the theory of poetry (its forms, histories, critical categories) it is also the theory of poiesis (of making), and this larger field draws it beyond the boundaries of poetry as a specifically literary activity. As we study this tension between poetry and poiesis, we want to document its contemporary transformations by publishing texts that have shifted and sharpened the focus of our attention to philosophical problems, embodied histories, political contradictions, artistic experiments, and scientific models of structures and form.” Produced in an edition of two hundred and fifty copies, Thee Display, as well as other volumes produced through the series, is freely available on the Centre’s website. On first reading, the fragmented and theory-driven poetic of Thee Display appears to exist as a deep study of translation, examining the limitations of translating knowledge, form and theory as well as the breakdown of transcription and legibility. Fulton writes on philosophy and constellations, the death of her dog, the external and the internal, power and its relations, and a variety of transcription errors, working exactly what her opening piece suggests she was going to: attempting to salvage a text from broken digitization, including commentary and, when necessary, filling in the gaps. Hers is a translation of fragments, keeping the inarticulations and misreadings, akin to Anne Carson working through the remnants of Sappho, or the scraps of text Emily Dickinson composed on bits of envelope, displayed in full through The Gorgeous Nothings (New York NY: New Directions, 2013), edited by Jen Bervin and Marta Werner. Whether constructed, salvaged or misread, Fulton puts the misreadings and mistranslations on full display, allowing scraps to remain as scraps. Fulton explores conversion, digitization and loss, and how information breaks down and shifts between forms, adapting through the translator’s work. There are echoes of Nathanael’s ongoing work in Fulton’s poetic, a way in which theory and language are pulled between two poles, existing in the between state: changing form, but not fully formed.” See my full review here.

37. Angela Szczepaniak, The Nerves Centre: The latest from Canadian poet Angela Szczepaniak, now the London-based Lecturer and Programme Director of the MA in Creative Writing at the University of Surrey, is The Nerves Centre (Montreal QC: DC Books, 2021), a book subtitled “a novel-in-performance-anxiety / in ten acts / 131 stanzas / 2417 phonetic utterances.” The author of Unisex Love Poems (DC Books, 2008) and The Qwerty Institute (Annual Report) (Toronto ON: Book*hug, 2012), Szczepaniak’s The Nerves Centre offers itself as “a series of poems about performance (and other) anxiety, told through the jittery stop-and-start actions of a stage fright-afflicted Performer who can’t speak while on stage. […] Constructed from recordings of actual panic attacks that were poorly transcribed by increasingly confused transcription software, then reshaped into poems for the page, these sound and breath pieces create a palpable experience of a Performer caught in the moment of panic.” The resulting text does result in a rather compelling visual text as a visual transcript of a combination of sound poem and stuttered performance, halting a staccato across the page. The Nerves Centre plays with stage direction, sound and stress, performance, the structures of self-help, signs and abrupt and halting phrases that stretch and accumulate, sometimes uncomfortably, across not only the page but across silences and held breath. “speaker skips toward microphone,” she writes, opening “Act 7,” “bright readied [.]” It is interesting to see how Szczepaniak has shifted what is usually seen as a detriment to performance and crafting a performance through that lens, akin to Jordan Scott utilizing his stutter into the performance-utterance of his poetry collection blert (Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2008). If Scott’s project asked “What is the utterance?” then Szczepaniak’s The Nerves Centre explores her own pauses, hesitations and halts to ask a similar series of questions. What is the utterance? What is the performance? See my full review here.

38. Liz Howard, Letters in a Bruised Cosmos: A follow-up to her Griffin Poetry Prize-winning debut, Infinite Citizen of the Shaking Tent (Toronto ON: McClelland and Stewart, 2015) is Toronto poet Liz Howard’s second poetry collection, Letters in a Bruised Cosmos (McClelland and Stewart, 2021). The poems of Letters in a Bruised Cosmos are formed and shaped out of lyric narratives, bursts of trauma, recollection and meditation, constructed as an assemblage of fragments that pool together to form a singular work. Her poems unpack, resolve and document the ways in which she attempts to reconcile the facts of a father who abandoned her. It is only as an adult that she finally catches up to him, mere days away before he died. As she writes, further, in the suite “LETTER FROM HALIFAX”: “Two days I have been / in Halifax. Two days since my father has passed / from mystery into appearance, laying bare / his totality on a death bed, distended cirrhotic belly / and ethereally beautiful face.” Letters in a Bruised Cosmos presents itself as reportage, composed mid-way through an open-ended study around grief, identity and the cosmos, showing neither the beginnings nor the final results. Howard seeks to understand the world, herself and her place, seeking as much safety in herself and a better understanding her own identity. It is as though, through Howard, poetry is the form through which one can best navigate a comprehension of all things, from one’s own personal history to the structures of the universe. Despite any upheavals through her past, Howard is a poet with a confident and considered foot pounding down against the foundations, not only seeking but demanding ground. “History is a sewing motion / along a thin membrane.” she writes, as part of the poem “BRAIN MAPPING.” A few lines further down, in the same poem, ending that particular section: “Can I still learn / to feel protected / by what encloses me?” See my full review here.

39. Leanne Dunic, One and Half of You: West Coast writer and musician Leanne Dunic’s latest, following To Love the Coming End (Toronto ON: Book*hug/Chin Music Press, 2017) and The Gift (Book*hug, 2019), is the long poem lyric memoir One and Half of You (Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2021). One and Half of You is a treatise on sibling love, and seeking a space of comfort and comprehension; an examination on identity and growing up. A book-length collection of lyrics that accumulate across a narrative around mixed-race identities, gender and sexual preference, Dunic writes a fragmented composed of short bursts, prose knots and breaths. Dunic writes on growing up into and against a set of expectations that don’t quite fit, experiencing homophobia and racist presumptions and attacks and dismissals. Dunic’s small sections focus on the intimate, seeking to articulate a mapping of how one gets to here. “Funny that the girl from my kindergarten / class remembers my Ghostbuster-crush / more than me kissing her nearly every day. / When I think of her, that’s what I remember.” The lyrics that make up One and Half of You are set as a long thread, nearly an endurance; a book that attempts to navigate the complications of self against shortsighted social limitations. “At recess,” Dunic writes, early on in the collection, “the older kids taunted, <are you a / boy or a girl?> I was pretty sure I was a girl / but didn’t understand why I wanted to kiss / boys and girls when I knew I wasn’t / supposed to. Gender didn’t matter. Age / didn’t either; I recall not just kissing my / classmates, but they grey-haired school / principal too. I loved to love.” See my full review here.

40. Megan Gail Coles, Satched: Poems: It is interesting to see Satched: Poems (Toronto ON: Anansi, 2021), the full-length poetry debut by the award-winning St. John’s, Newfoundland fiction writer and playwright Megan Gail Coles. Following her short story collection Eating Habits of the Chronically Lonesome (St. John's NL: Killick Press, 2015), he collection of plays for young audiences, Squawk (Playwrights Canada Press, 2017), and her Giller Prize-shortlisted novel Small Game Hunting at the Local Coward Gun Club (Anansi, 2019), the poetry collection Satched is an assemblage of lyric narratives named after “the state of being soaked through to the skin or caught in a heavy downpour.” Running at more than one hundred and thirty pages, this is a hefty collection of poems, and one that is constructed with a narrative propulsion. Coles is clearly, first and foremost, a teller of stories, and her scenes are assembled out of a sequence of sentences foundational in their love of music, tone and clatter. Satched is rooted (or, anchored) in Atlantic Canada; in island life, writing a Newfoundland of resilience and deep beauty, a population and landscape both battered up against the rocky shore by storms. Anchored, or even immersed, as the title suggests; there is no escaping it. This collection is composed, nearly, as a love letter to her home and its people, writing of wind and rage and minimum wage and the possibilities of joy. Satched is a collection composed as individual portraits assembled into a scrapbook of and around her eastern landscape with its endless nuances and complexities, writing the “weather-beaten eyes shadowing soft middles and harmed hearts” of the poem “HOW I GOT TO THIS PLACE,” the “affiliation to this place you never / visit and regularly swear off as backward, / full of idiots, inbreds and rednecks you don’t like / who don’t like you much either” from “FRESH NEOLIBERALS [.]” See my full review here.